For centuries, women and men have been training to breathe underwater, or "free diving." Indirect evidence comes from the origins of underwater artifacts found on land (such as mother-of-pearl patterns) as well as images of divers depicted in prehistoric drawings.

In ancient Greece, divers were known as sponge fishermen and were also involved in military action. In later years, the story of Scyllis (also pronounced Scyllias), which took place around 500 BC, is probably the most popular story by the Greek historian Herdotus, quoted in many contemporary works.

During the naval battles, the Greek Scylis was transported by ship outside the country as a prisoner of King Persia Xerexes I. When Scyllis discovered that Xerexes had attacked the Greek flotilla, he grabbed a knife and jumped overboard. The Persians could not find him in the water, so they thought he was drowned. Scyliss jumped up at night and made his way along all the ships in the Xerxesa fleet, cutting off their anchors, he used reeds as a scuba tube to remain invisible. He then swam nine miles (15 kilometers) until he joined the Greeks in the Artemisium cape.

People have always been tempted to go underwater, both to discover artifacts, to hunt for food, to repair ships (or to sink them), and to observe the underwater realm. Until a way to breathe underwater was discovered, diving was inevitably considered a short and insane process.

One of the main obstacles to diving is to be under water for a long time. Breathing through reeds allows the body to be immersed in water, however, reeds immersed deeper than two feet no longer give the desired result, the length of the tube makes it difficult to inhale under high water pressure. An air-filled bag was also used to deliver oxygen underwater, but the idea also failed because we had to inhale carbon dioxide after exhaling.

In the 16th century, people began to use a diving dome that was supplied with air from the surface, and it was also the first effective way to stay underwater for extended periods of time. The dome was held motionless a few feet above the ground, the underside of which was open in water, and the upper part contained air compressed by water pressure. The diver, standing upright, could keep his head in the air. He could leave the dome for one to two minutes to collect sponges, or explore the depths of the sea, then return for a short while to do so until the air in the dome was no longer breathable.

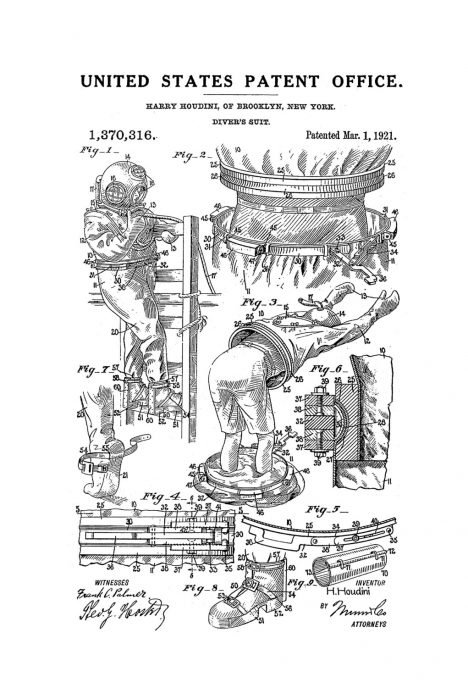

In the 16th century in England and France, full diving suits were made of leather, which were used for diving to a depth of 60 feet. The air was pumped from the surface by hand pumps. The helmets were then made of metal to withstand the increasing pressure of the water, and divers could go deeper. In the 1830s, the supply of air to the helmets from above was improved to allow for versatile rescue operations.

In the 19th century, two main research paths began - one scientific, the other technological, which accelerated underwater research. Research was facilitated by the work of Paul Bert (France) and John Scott Halden (Scotland). Their research helped explain the effects of water pressure on the body and defined the safety limit for compressed air diving. At the same time, technological improvements - compressed air pumps, carbon dioxide purifiers, regulators, etc. - allowed people to stay under water for a long time.